Wine

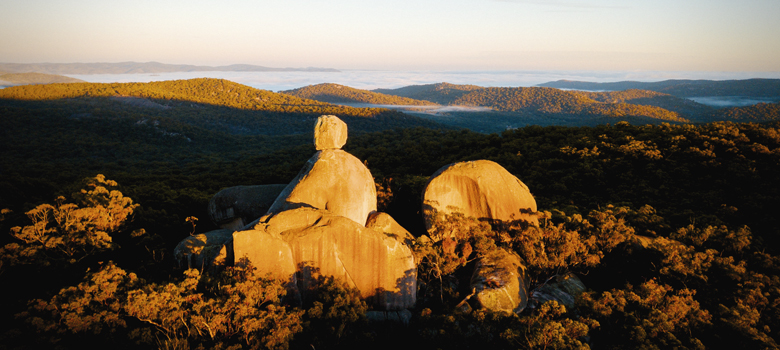

Queensland's Granite Belt

Just two and a half hours' drive from Brisbane, you'll gain a whole new perspective on Queensland, one that's cool in terms of both its weather and its wine.

The Granite Belt is one of Australia’s most unusual wine regions, and its ‘strange bird alternative wine trail’ is one of the most diverse you could explore.

Shop Best Australian Wine

On a 2.5 hour drive from Brisbane, coastal lowlands give way to tablelands with unusual granite outcrops, dramatically beautiful national parks, and a patchwork of stone-fruit orchards, vineyards and fields growing strawberries, rockmelon, tomatoes…you name it. As well as the chance to fossick for wine gems, tasting at its 40 or so family-owned winery cellar doors, the Granite Belt has plenty to discover in the way of fine food based on fresh local ingredients (Hint: try Essen and Varias restaurants, St Jude’s Bistro, and the storybook giant apple pies at Suttons Shed Cafe).

Stanthorpe, the Granite Belt’s largest town, is on the same latitude as Byron Bay, but its famous ‘alternatives’ are not dreadlocked hippies, but rare grape varietals, and the climate is definitely not subtropical. You may even discover a potbelly stove in your boutique accommodation – coastal Queenslanders love coming here to swap heat and humidity for wood fires, crisp nights, and occasional snowfalls.

College of Cool

As befits a wine tourism destination par excellence, one where most of the wines created are purchased at the cellar door, the Granite Belt even boasts a College of Wine Tourism, the only one in the world. Sharing grounds with Stanthorpe High School, the college has a restaurant, Varias, serving seasonal delights and its Banca Ridge wines, made on the premises. The college teaches all-comers: from high-school up to tertiary level, in winemaking, viticulture, wine operations and hospitality skills, as well as ‘winemaker for a weekend’ courses. The Banca Ridge winemaker, Arantza Celador, born and educated in Spain, is trialling new wines from the college’s experimental ‘Vineyard of the Future’, as well as teaching and winemaking. She is really excited to see reactions to the next two varieties she’s making for the wine list, Tinta Cao and Albariño: “Especially Albariño, since it is a Spanish grape variety,” she says.

Tableland Terroir

The hilly terrain means vines can be grown on slopes at differing orientations to the sun, at altitudes from 600 to 1000 metres high, on free-draining sandy soils that “have a greater tendency to throw wines that are rather acidic and rather aromatic,” a feature of Granite Belt wines, “the whites in particular,” according to Peter O’Reilly, CEO of the College of Wine Tourism. The continental climate means days are not too hot in summer, and the overnight minimum is an average of 13°C, which slows the chemical changes occurring in the grapes.

“It lengthens the ripening period,” O’Reilly says, “and the longer the ripening period, the better the flavour development.”

O’Reilly thought the Granite Belt wines were undrinkable when he first visited in the 1990s, “because I was used to, say, Barossa Shiraz, which is a great big high-alcohol fruit bomb, very soft,” he explains. “Here, you’d get a Shiraz that was medium-bodied and peppery, just completely different,” he says, “and while our Shiraz might be far more like a French Syrah, I wasn’t to know that then.”

Not only do mainstream wine favourites develop distinctive qualities here, the Granite Belt has become a hothouse for developing alternative wines: mostly Mediterranean, some very hardy, many flourishing in this terroir. The Granite Belt’s alternative wine trail, featuring ‘strange bird’ varieties, is helping to educate the palates of its visitors.

Strange Birds

The locals define a strange bird in the Granite Belt Wine Trail Map as a wine grape represented by “not more than one percent of the total of bearing vines in Australia,” (as measured by Wine Australia). The trail map showcases 31 wineries and their top wines, both popular ones such as Shiraz, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, but also the strange birds, 11 whites and 15 reds, of various levels of obscurity. You may know of Verdelho, Marsanne, Petit Verdot and Tempranillo, but maybe not Poussane, Petit Manseng, Tannat and Alvarinho; or, at least, not their Australian incarnations.

On occasion, strange birds can drop off their perch, that is, off the map, when the extent of their nation-wide mature plantings goes over the limit. “We’re very strict about the one percent,” says Ridgemill Estate winemaker Peter McGlashan, co-inventor of the strange bird concept. They are passionate about appellation also: “The wines must be made from 100 percent Granite Belt-grown grapes, that’s very important,” McGlashan says.

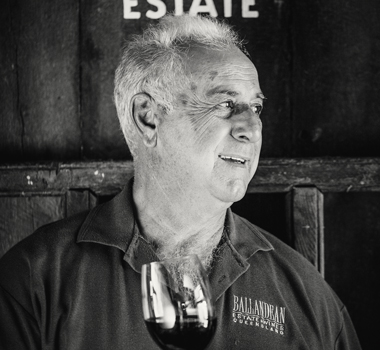

Some strange birds have landed by happy accident, as when Ballandean Estate founder Angelo Puglisi received wrongly-labelled cuttings which turned out to be Silvana, for which Ballandean has won awards ever since. Robert Channon lost his first Chardonnay vines order when a nursery sold these to another customer, and “at the very last moment, we had to take Verdelho from them instead.”

While Robert Channon went on to win national awards for Chardonnay, the winery is also “arguably Australia’s foremost producer of Verdelho,” according to wine critic James Halliday. Argentinean born, Spanish-trained Paola Cabezas-Bono, the current winemaker, is very experienced with one of the winery’s other strange birds, Malbec, the icon of Argentinean wines.

Super Saperavi

Not to throw shade on the many other discoveries you may encounter on the trail – Malvasia, Viognier, Vermentino spring to mind – but the grape really shaking things up here is Saperavi (the name means ‘tint’ or ‘dye’, in reference to its red flesh). This hardy varietal is as ancient as the winemaking traditions in its homeland of Georgia. For 8000 years, Georgian villagers have fermented their wines in clay barrels (qvevri) buried in the ground, and Saperavi is their favourite

grape. It’s also reaching cult status among some Australian wine aficionados.

“We first saw it here in 2004 at Stanthorpe’s national Small Winemakers Show,” says Martin Cooper, the owner of Ridgemill Estate, who fell in love and was the first to plant it locally. “The flavours are so intense…dark chocolate, liquorice, spices,” he says. “It’s just an incredible wine.”

Others followed his example. In 2017, Georgia, flushed with national pride after its qvevri winemaking was recognised by UNESCO as part of the ‘intangible cultural heritage of humanity’, hosted a World Saperavi competition in the capital, Tbilisi. Twenty-seven winemakers from seven countries were invited to take part, and three Granite Belt wineries, Ridgemill, Ballandean and Symphony Hill, scored four awards

between them.

In the past year or so, the Granite Belt has faced tough times: severe drought (the 2020 harvest was way down), plus bushfires, and then Covid-19, which has affected tourism, hence sales. Yet this region’s passionate winemakers are not only persevering, but perhaps setting an example by their devoted experimentation with varieties that may serve Australia well as the climate changes. For example, despite the last year of drought hardship, Ridgemill Estate will plant more Saperavi when rootstock arrives this September. As Queensland’s borders reopen, it might be time to take your palate on a trip.